In a groundbreaking study, researchers at the University of Texas have delved into the intricate connection between the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and multiple sclerosis (MS), shedding light on the elusive trigger behind this autoimmune disease affecting around 36 people in every 100,000 worldwide.

EBV, a common virus infecting most individuals at some point in their lives, has long been suspected as a potential catalyst for MS. The challenge for scientists has been deciphering the precise mechanism through which the virus prompts the immune system to attack the body’s own cells, often manifesting symptoms years after the initial infection.

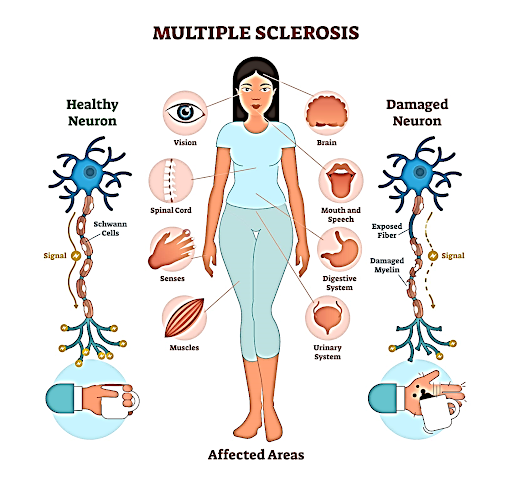

The research takes a significant step forward in understanding the early stages of MS, where symptoms have surfaced but a formal diagnosis may not have been made. MS is characterized by the immune system mistakenly attacking the protective sheath, called myelin, covering nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord.

Previous studies hinted at molecular mimicry between EBV proteins and molecules in the brain and myelin, setting off a cascade of confusion within the immune system. B cells, a type of white blood cell, produce antibodies that mistakenly tag the wrong molecules for destruction.

To unravel the role of T cells, another vital component of the immune system, in the context of EBV and MS, researchers examined interactions between T cells in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of eight individuals with early MS symptoms. By sequencing the receptors on the T cells’ surface, they explored recognition patterns for EBV-infected cells and other common viruses.

Results revealed a significant presence of T cells designed to recognize EBV-infected cells, particularly in the CSF at the earliest MS stages. “This strongly suggests that these T cells are either causing the disease or contributing to it in some way,” explains J. William Lindsey, a neurologist at UTHealth.

While some experts describe these findings as ‘smoking gun evidence’ for the role of EBV in MS, it’s essential to note the study’s small sample size. Nevertheless, smaller studies play a crucial role in unveiling intricate mechanisms, complementing larger studies searching for broader patterns.

The implications extend beyond MS, as EBV has also been linked to chronic fatigue syndrome (myalgic encephalomyelitis, or ME/CFS). For a virus so common, the havoc it may wreak on our health is indeed remarkable. As researchers continue to piece together this complex puzzle, the study opens a promising chapter in our quest to understand and combat autoimmune diseases.

© 2024 Rivantosh Edupedia by Inspiring Web Designs • All Rights Reserved. • Privacy Policy • Disclaimer